Wind Speed Limits for Rocket Launches

Share

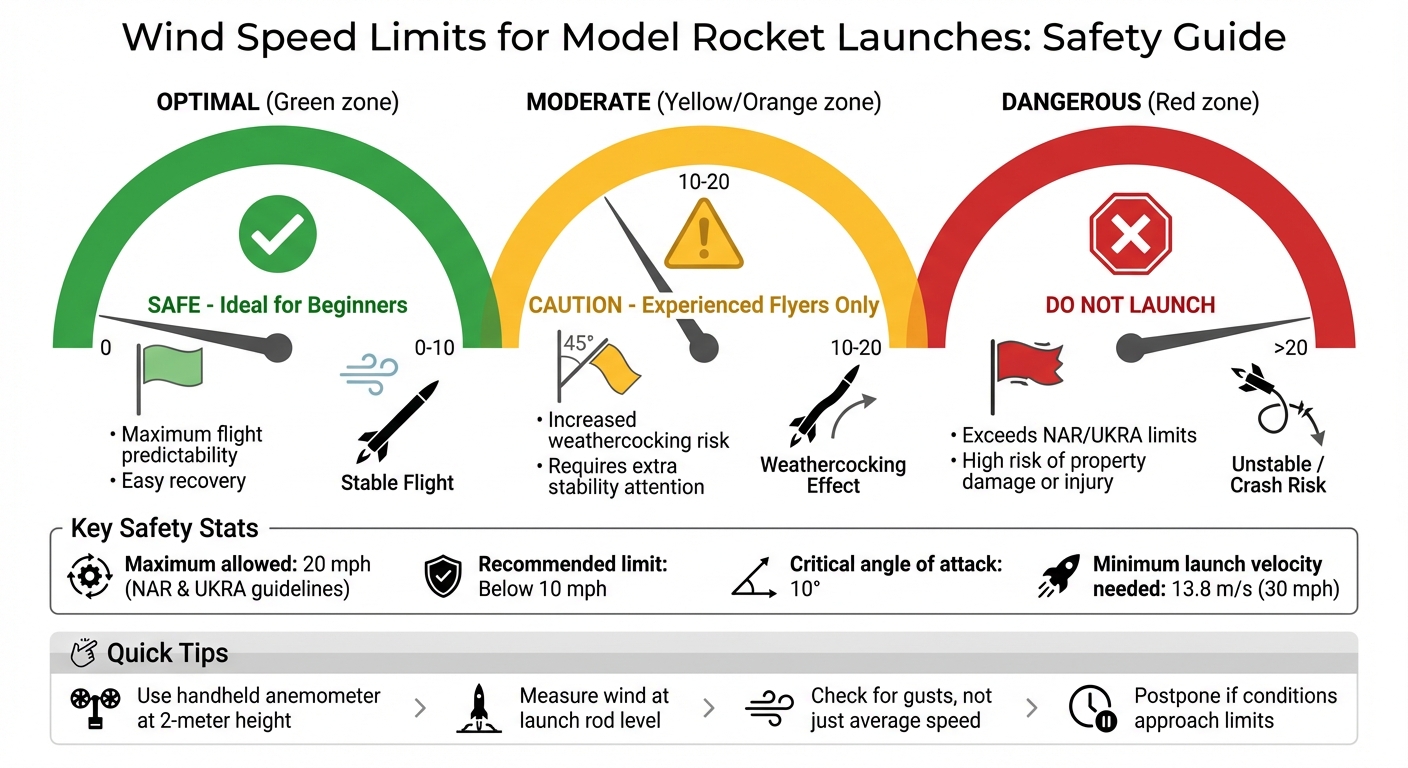

Wind can make or break a model rocket launch. Strong winds risk pushing rockets off course, causing instability, or even leading to dangerous situations. To ensure safety:

- Maximum Wind Speed: 20 mph (as per UKRA and NAR guidelines).

- Recommended Wind Speed: Below 10 mph for safer and more predictable launches.

- Weathercocking Risk: High winds can tilt rockets into the wind, affecting stability and trajectory.

Key Tips:

- Use a handheld anemometer to measure wind speed near the launch site.

- Check wind conditions at the rocket's launch height (about 2 metres).

- Avoid launching if wind gusts exceed safe limits.

Safety comes first - always follow guidelines to protect people, property, and your rocket.

Wind Speed Safety Limits for Model Rocket Launches

Wind Speed Limits for Model Rockets

Why Wind Speed Limits Matter

Wind plays a huge role in your rocket's trajectory and where it lands. When wind speeds get too high, the aerodynamic forces acting on the rocket can push it off course. This often causes the rocket to turn into the wind - a phenomenon known as weathercocking.

If the rocket's angle of attack goes beyond 10° during launch, the centre of pressure can shift ahead of the centre of gravity. This throws off the rocket's balance, leading to unstable flight. The result? Your rocket might violently pitch back and forth (commonly referred to as "sky-writing") or, worse, dive straight into the ground in what's called a "lawn dart" effect.

"Weather cocking occurs when aerodynamic forces on the model rocket cause it to turn into the wind. The model rocket could move far away from the launch site and damage nearby property or hurt one of your students." - AC Supply Co

High winds also make descents unpredictable, with rockets potentially drifting kilometres away from the launch point.

Standard Wind Speed Thresholds

The National Association of Rocketry (NAR) Safety Code sets a maximum wind speed of 20 mph (about 17.4 knots) for model rocket launches. Similarly, the United Kingdom Rocketry Association (UKRA) enforces the same limit, and all pyrotechnic rocket launches in the UK must adhere to UKRA's Safety Code requirements.

| Wind Condition | Speed | Impact on Launch |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal | Below 10 mph | Ideal for beginners, offering maximum flight predictability. |

| Moderate | 10–20 mph | Increased risk of weathercocking; requires extra attention to rocket stability. |

| Dangerous | Above 20 mph | Exceeds NAR/UKRA limits; poses a high risk of property damage or personal injury. |

Experienced rocketeers often set their own stricter wind limits. Many prefer waiting for wind speeds to drop below 10 mph for safer launches and easier rocket recovery. This is particularly important for beginners, lightweight rockets, or when launching in areas with limited recovery space. If wind speeds approach the 20 mph maximum, postponing the launch is always the safest option.

Next, we’ll look at how to accurately measure wind speeds at your launch site.

sbb-itb-f093e97

How to Measure Wind Speed at Your Launch Site

Using an Anemometer

A handheld digital anemometer is a reliable tool for checking wind speed at your launch site. Cup anemometers are great because they measure wind from any direction, while propeller-style anemometers are a more budget-friendly option but need to be aligned directly with the wind to work properly.

For the most accurate reading, measure wind speed at the height of your launch rod, which is typically about 2 metres. This ensures you account for the "ground effect", where wind behaves differently near the surface compared to higher up [3,12]. Handheld anemometers are an affordable investment for regular launches, with prices ranging from £12 to £35.

Visual Indicators for Wind Assessment

If you don’t have an anemometer, you can estimate wind speed using visual clues and the Beaufort scale. For example, rustling leaves suggest a light breeze of about 4–6 knots, while small branches moving indicate a moderate breeze of 11–16 knots. If trees are swaying, the wind is likely near-gale force (28–33 knots), which makes launching unsafe.

Flags are another handy indicator. A flag hanging limp means calm conditions, while a flag extended but not flapping points to a light breeze. If the flag is fully extended and flapping vigorously, it suggests a fresh breeze of 17–21 knots, which is close to the 20 mph safety limit for launches. You can also try the "paper drop" method: drop a piece of paper from a height of 2 metres. If it lands about 2 metres away, the wind speed is roughly 1 m/s.

Timing Your Measurements

Always measure the wind speed just before launch, as conditions can change quickly [3,4]. While professional weather stations measure wind every 0.25 seconds, on-site measurements are sufficient for model rocketry. The Met Office suggests averaging wind speed over 10 minutes for a more reliable reading. If your anemometer shows speeds close to the 20 mph limit, it’s best to wait for a calmer window.

It’s also a good idea to check local weather forecasts the night before and on the morning of your launch. However, always prioritise on-site readings over forecasts, as they provide the most accurate picture of current conditions [3,4].

These methods will help you better understand wind patterns and variability at your launch site.

Wind Gusts and Variability

Wind Gusts vs Average Speeds

Understanding the distinction between sustained winds and gusts is crucial for safe rocket launches. Sustained wind speed refers to the average speed measured over a ten-minute period, while a gust is defined as the highest three-second average wind speed recorded during that time frame. The Met Office samples wind data every 0.25 seconds to capture these brief but intense peaks.

Gusts can dramatically increase a rocket’s angle of attack (AOA) during launch. A sudden gust may push the AOA beyond safe limits, leading to instability, as previously discussed. Because of this, it’s essential to consider peak gust speeds, not just average wind speeds, when evaluating launch conditions.

"One 'rule of thumb' for launching is that we want the rocket to have a minimum velocity of around 13.8 m/s (around 30 mph) as it leaves the launch rod... that is the speed at which the air will push hard enough on the fins to keep the rocket pointed in the direction you want it to go." - Ian Voss, Rocketry Enthusiast

Wind Conditions at Altitude

While ground-level gusts are a key factor, it’s also important to account for how wind conditions change with altitude. As height increases, wind speeds generally rise, and the direction can shift significantly. Ground-level measurements provide a starting point, but the conditions at higher altitudes are often stronger and less predictable. These changes can influence the rocket’s trajectory and affect where it ultimately lands.

When to Postpone a Launch

Considering the variability in wind conditions at different heights, it’s essential to make cautious launch decisions. UKRA guidelines state that rockets must not be launched in winds exceeding 20 mph, with a recommended limit of 15 mph. If your anemometer frequently registers gusts nearing these limits, it’s wise to delay the launch. Similarly, if maintaining an AOA below 10 degrees becomes challenging or if the launch rod visibly flexes in the wind, it’s better to wait for calmer conditions. Safety should always come first. Up next, we’ll examine how these wind factors influence rocket stability during flight.

Rocket Stability in Wind

Rocket Design and Stability

For a rocket to remain stable, its centre of gravity (CG) must stay ahead of its centre of pressure (CP). When wind hits the rocket from the side, it can push the CP forward. If the CP moves ahead of the CG, the rocket risks tumbling or crashing.

The static stability margin, measured in calibres, represents the distance between the CG and CP. In calm weather, a margin of 1 calibre might be enough, but in windy conditions, a margin of at least 2 calibres is recommended. You can achieve this by adding weight to the nose or increasing the fin size. These adjustments lower the CP while also increasing the rocket's rotational inertia. Additionally, longer rockets with weighted noses are less likely to veer off course when hit by gusts.

Now, let's explore how wind affects the rocket's alignment and the need for launch angle adjustments.

Weathercocking and Launch Angle Adjustments

Weathercocking is a phenomenon where the rocket naturally turns into the wind due to aerodynamic forces. When wind strikes the rocket, it creates a side force that generates torque around the CG, causing the rocket to rotate until its nose aligns with the wind. However, this alignment comes at a cost: the rocket's trajectory tilts away from vertical, reducing its maximum altitude.

The extent of weathercocking depends on how fast the rocket is moving compared to the wind. A higher launch velocity helps minimise this effect, keeping the flight path closer to vertical. To counteract descent drift caused by wind, it's a good idea to angle the launch rod slightly into the wind.

Launch Velocity Considerations

Getting the rocket to a sufficient speed right after liftoff is crucial to maintaining stability. The widely accepted minimum velocity for stability is 13.8 m/s (about 30 mph). At this speed, the aerodynamic forces acting on the fins become strong enough to properly guide the rocket's flight. If the rocket doesn't reach this speed quickly, crosswinds can push it off course before the fins can take control.

| Design Feature | Impact on Windy Stability |

|---|---|

| Added Nose Weight | Raises the CG, increasing stability margin and improving resistance to sudden gusts. |

| Increased Fin Area | Moves the CP rearward and provides better aerodynamic damping, reducing wobbling. |

| High Thrust-to-Weight | Boosts liftoff speed, minimising the rocket's initial angle of attack from crosswinds. |

| Longer Launch Rail | Extends the guided acceleration distance, reducing exposure to crosswinds at liftoff. |

For windy launches, select motors with high initial thrust and short burn times. Aim for a thrust-to-weight ratio of at least 10:1 to quickly achieve the minimum velocity of 13.8 m/s. This reduces the time the rocket is vulnerable to crosswinds. Using a longer launch rod or rail also gives the rocket more distance to accelerate while still under guidance, improving stability once it encounters open wind.

Safety Protocols and Site Conditions

Site Selection and Setup

When choosing a launch site, look for an open area with clear views both upwind and downwind. Make sure you have permission from the landowner, and ensure the location is at least 5 km from airports and 1 km from coastal or flare areas. The launch rod should be positioned no more than 20° from vertical, and a 3-metre radius around the launch area must be cleared of any flammable materials. Always have fire extinguishing equipment on hand. If public footpaths cross the site, implement a system to pause activities whenever non-participants enter the area.

Additionally, keep a close eye on weather conditions throughout the launch session to maintain safety.

Monitoring Weather Conditions

Weather can change quickly, so continuous monitoring is crucial during your launch. A Range Safety Officer (RSO) must inspect every rocket and has the final say on whether to delay or cancel launches based on weather conditions. This includes checking wind speeds not only at ground level but also at the rocket's expected peak altitude to ensure safe recovery and dispersal.

Keep the rocket in sight from at least two seconds before launch until it lands. In the event of a failed ignition, wait at least one minute for low-power rockets or three minutes for high-power rockets before approaching the launch pad.

Finally, ensure that all activities comply with UK regulations to complete your safety measures.

Regulatory Compliance for UK Launches

All launches in the UK must adhere to the Air Navigation Order (ANO) 2016, particularly Articles 96 and 240, which govern rocket operations and prohibit endangering aircraft safety. If your rocket is expected to exceed 120 metres (400 feet) above ground level, you’ll need to submit a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) to the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) at least 28 days in advance.

Operators are required to minimise risks to the public and property, following the principle of "As Low As Reasonably Practicable" (ALARP). Rockets with a total motor impulse exceeding 10,240 Newton-seconds need "Large Rocket Permission" from the CAA, although there is currently no fee for this application. It’s also a good idea to have insurance in place - coverage for rocketry activities is available through the British Model Flying Association (BMFA), provided you follow the UKRA Safety Code.

| Motor Class | Total Impulse (Ns) | Min. Distance (Single Motor) | Min. Distance (Multiple Motors) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Up to 2.5 | 2m | 3m |

| B, C | 2.5–10 | 3m | 6m |

| D | 10–20 | 5m | 10m |

| E | 20–40 | 7m | 15m |

| F, G | 40–160 | 10m | 20m |

| H | 160–320 | 15m | 30m |

Source: UKRA Safety Code

76 - Wind Weather Cocking

Conclusion

Respecting wind speed limits is a cornerstone of safe model rocketry. The 20 mph maximum threshold exists for a reason: beyond this, weathercocking becomes more severe, and recovery can spiral into unpredictability. That’s why seasoned enthusiasts often prefer launching in winds below 10 mph, ensuring greater control and a more enjoyable experience.

"Safety is the concern of all present and is the shared responsibility of all." – UKRA Safety Code

To get accurate wind data, rely on a handheld anemometer rather than standard weather forecasts. For stability, make sure the Centre of Pressure is positioned at least one body tube diameter behind the Centre of Gravity.

Launch velocity is another key component. Your rocket should leave the launch rod at about 13.8 m/s so the fins can do their job effectively. If winds exceed 10 mph, consider upgrading to more powerful motors and using longer launch rods to hit this critical speed. Pairing this with strict adherence to safety guidelines ensures a smoother and safer launch.

In short, always trust your Range Safety Officer's judgement and keep visual contact with your rocket from two seconds before lift-off until it lands. By combining accurate wind readings, sound design principles, and a commitment to safety, you can ensure every launch is both safe and rewarding.

FAQs

What is weathercocking, and why is it important for rocket launches?

Weathercocking occurs when a model rocket tilts into the wind shortly after launch due to aerodynamic forces acting on its body. Essentially, crosswinds create a horizontal airflow that causes the rocket to pivot and align with the wind, much like a weather vane.

This phenomenon can lower the rocket's maximum altitude because part of the thrust is diverted to turning rather than climbing. It can also result in the rocket drifting away from the launch site, complicating recovery and increasing safety concerns. For safer launches, it's best to avoid winds exceeding 32 km/h (20 mph) and aim for calmer conditions - ideally below 16 km/h (10 mph) - to reduce the chances of weathercocking.

To improve safety and launch success, opt for stable rocket designs, position launch pads appropriately, and keep a close eye on wind conditions. Programmes like Rocketry for Schools provide excellent kits and tools, helping students learn how to measure wind speeds and execute safe launches while minimising the effects of weathercocking.

Why is it important to measure wind speed at the rocket's launch height?

Measuring wind speed at the rocket's launch height is crucial because wind conditions can change dramatically between ground level and just a few metres above. Even if the wind seems calm on the ground, it can pick up significantly at launch height. This can lead to a phenomenon known as weather-cocking, where the rocket is pushed off course by the wind. Such unpredictable flight paths not only increase the chance of the rocket drifting far from the launch site but also raise the risk of accidents or damage.

Wind speed at launch height plays a key role in determining the forces acting on the rocket during its ascent. Stronger winds create more sideways pressure, making it harder to keep the rocket on a stable trajectory. For safety and control, it’s essential to measure wind speed at the height of the launch pad - usually just a few metres off the ground - and ensure it stays within the safe limit. For most model rockets, this is generally no more than 16 km/h (10 mph).

If you’re using a Rocketry for Schools launch kit, you’ll find an anemometer included. This handy tool lets you accurately measure wind speed at the pad height, helping you make well-informed decisions before hitting the launch button.

How can I keep my model rocket stable in windy weather?

To keep your model rocket stable in windy weather, it's all about getting the centre of gravity (CG) and centre of pressure (CP) just right. For a smooth flight, the CG should always sit ahead of the CP. You can adjust this by adding a bit of weight to the nose, opting for larger fins, or extending the length of the fins. Before you launch, double-check the CG by balancing the rocket to confirm it's in the proper position.

Even with a perfectly balanced rocket, strong winds can create problems. It's best to avoid launching if the wind speed is over 32 km/h (20 mph), and for safer conditions, aim for speeds under 16 km/h (10 mph). To assess the wind on launch day, use tools like a handheld anemometer or a windsock. If the wind seems too strong, it’s always better to delay the launch.

For schools and clubs, Rocketry for Schools offers kits and accessories that incorporate these stability principles. Their products are designed to simplify rocket building, ensuring reliable performance, even in the unpredictable UK weather.